Peter Harvey posts…

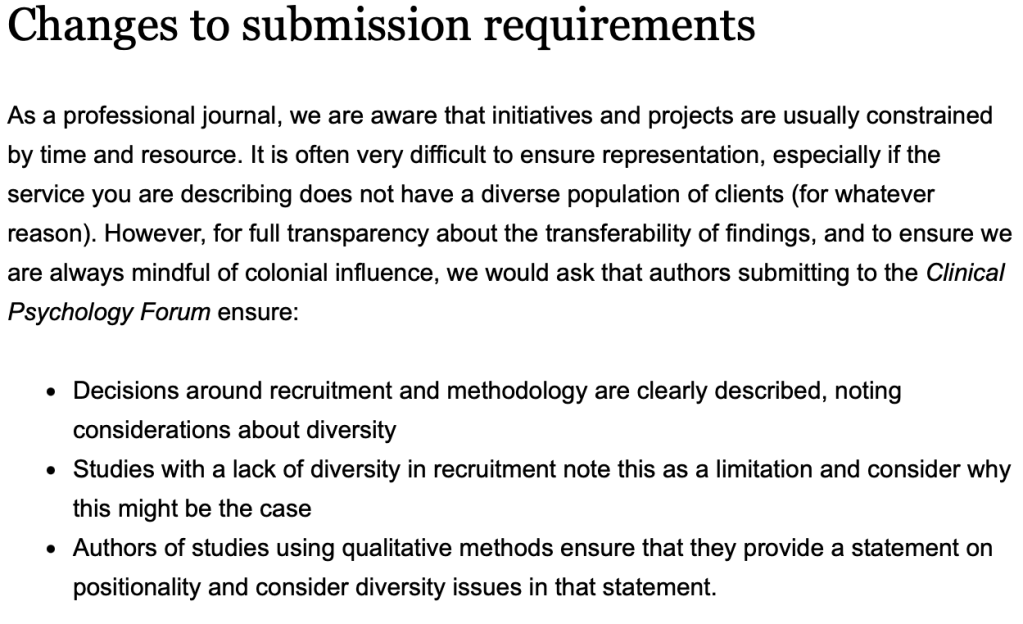

Below is a screen shot from an email I received recently from Clinical Psychology Forum (CPF) which outlines its revised guidance for submission of articles:

You will have your own opinions, thoughts and raised eyebrows about this but here are some of my observations.

My first impression is that this is incredibly patronising. Understanding sample selection and generalisability is a fundamental element of research design. Are the editors seriously suggesting that doctoral level graduates and trainees do not have this knowledge? Likewise the comment on ‘positionality’ in qualitative work. When I was examining some 25 or more years ago and these methodologies were becoming more common, it was a sine qua non that the investigator engaged in multiple and frequent reflections on the material and their interaction with it. Why do people need reminding of this? Perhaps I am missing something here. Is it that CPF is actually getting submissions that have to be rejected for such basic errors? If so, it suggests a more serious problem – that research design and methodology are not being properly taught and supervised either at an undergraduate level or during clinical training. I am far too distant from it all to know the answer to that so it would be interesting to get a view from those currently involved.

There are two words, however, that (in the modern parlance) are triggers for me – ‘diversity’ and ‘colonial’. Starting with diversity I am absolutely not arguing with a principle that treats all humans as equal and that discrimination on the grounds of, for example, race or sex is fundamentally and morally wrong. Nor am I disputing that people are excluded and discriminated against historically and currently both in society at large and in the psychological research literature. Nor do I deny that much of the history of European colonialism is shameful. These are moral positions supported (in my case) by a strong humanist philosophy. But if I am engaged in a research exercise then what needs to guide my thinking is “What method or procedure do I need to employ that will give me at least an approximate answer to the research question that I am asking?”. This is not an ethically neutral question, of course, as a flawed design will produce flawed results which, if inappropriately applied, may cause harm. As participant characteristics and sample selection are an integral part of that process then it should go without saying that this is guided by the same ethical and moral principles as the rest of the project. In fact, the BPS’s Code of Human Research Ethics (2021) is explicit:

Section 2.1, Respect for the autonomy, privacy and dignity of individuals, groups and communities

Psychologists have and show respect for the autonomy and dignity of persons. In the research context this means that there is a clear duty to participants. For example, psychologists respect the knowledge, insight, experience and expertise of participants and potential participants. They respect individual, cultural and role differences, including those involving age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity race (including colour, nationality, ethnic or national origin), religion and belief, sex, sexual orientation, education, language and socio-economic status.

That seems pretty clear to me, so what does emphasising “diversity” add? All the editors of CPF need to do is to require that all submissions follow the BPS Code – job done.

Once the research is completed it is always incumbent on an investigator to highlight the limits to their data and for the reader to be equally alert to the dangers of over-generalisation. This is no more than good practice.

There is a further question which relates to the diversity of the population from which you are sampling. When I was part of a selection team for a clinical training course we, along with others in the profession as a whole, were concerned about the ethnic diversity of trainees. The problem for us was that the ethnic diversity of psychology graduates was (at that time at least) poor. However much one wants to strive for diversity (however defined) there are factors that are beyond our control.

Apart from that, we need to ask the question – how diverse is diverse? Do we select from the ever-expanding categories on a random basis or just pick the one that happens to be most fashionable at the current time? Do we pick one of each? Will we need a sort of diversity quotient threshold that all published work has to reach? Or do we do what seems to happen with monotonous regularity – have some token representation that simply ticks the box so we can get on with our lives comfortable that we have assuaged at least some of our guilt? Surely the diversity to be aimed for is the one that is most representative of the group to which we want to generalise rather than engaging in a performative exercise?

But it is the phrase “…mindful of colonial influence…” that really got me scratching my head. What does that mean in operational and behavioural terms? What would I, a researcher, have to do in actual practice, to demonstrate that I am mindful of colonial influence? Is this a test of my knowledge of British and European history? And what exactly does the phrase “…mindful of…” mean? And, whose colonial influence do we include? The exhortation assumes that all clinical psychologists share the same colonial history. Whilst the profession may not be as diverse as the general population of the UK I know that not everyone shares the same background as me. So would a psychologist from a different ethnic or cultural background to me (perhaps someone from one of the historic colonies) have a waiver? Or would a clinical psychologist qualified in Holland need to be mindful of the actions of the Dutch East India Company? Should a Christian psychologist be mindful of the Crusades? Perhaps all submissions need to be accompanied by statement from an independent asssessor to the effect that they have witnessed and can attest to the fact that the experimenter did in fact, reflect mindfully on colonial influence for the prescribed 30 minute period ( I am happy that CPF use this freely and without authorial credit).

But perhaps I am being too literal here and a more nuanced and sophisticated reading of colonial influence is required. In his endlessly entertaining and intellectually sparkling book After Theory, Terry Eagleton argues that post-colonial studies have “… been one of the most precious achievements of cultural theory…” despite his observation that

… some students of culture are blind to the Western narcissism involved in working on the history of pubic hair while half the world’s population lacks adequate sanitation and survives on less than two dollars a day. [page 6]

He goes on to be much more critical and places this particular approach within a wider critique of post-modernism generally (in my view the book should be required reading on training courses). But his phrase Western narcissism is perhaps key here and is what the editors are trying to address. I interpret that as questioning the assumptions that we make as post-Renaissance liberal Europeans about our shared culture and heritage which usually lead to a sense of intellectual, moral and ethical superiority. This stance, of course, devalues other cultural norms and values.

Cultural relativism is a key element of of post-modernism, a definition of which is provided by Eagleton…

By ‘postmodern’ I mean, roughly speaking , the contemporary movement of thought which rejects totalities, universal values, grand historical narratives, solid foundations to human existence and the possibility of objective knowledge. Postmodernism is sceptical of truth, unity and progress, opposes what it sees as elitism in culture, tends towards cultural relativism, and celebrates pluralism, discontinuity and heterogeneity. [footnote, page 13]

This is not the place to engage in a critique of post-modernism (particularly as Eagleton does it so much better and with far greater wit and panache than I) but I do have some problems. In particular, this approach is often applied uncritically (an irony for so-called critical theory) and presents us with contradictory positions and yet further confusions. The Editors’ injunction demonstrates just such a problem.

Are they asking us to be aware of our colonial history or is it a more general reminder to be aware of our particular cultural values, of which colonialism may be a part? This certainly makes more sense to me. Taking a critical and questioning stance about making ‘cultural’ assumptions and decrying a position that assumes it is superior to others is not the problem. Where I struggle is in knowing how to deal with that in the real world out here. I suppose that part of it is (to my mind anyway) oversimplification – it’s almost as if it is “My culture bad, your culture good. I was the oppressor, you were the oppressed.”. There is no nuance, no ability to take a stance that says that there are both good and bad aspects of my culture as there are of yours. I suppose that some would argue that there is no equality or balance to be had as, historically, the balance has always been in favour of the colonialists and cultural supremacists. I am not going to take issue with that. But I still struggle when a particular culture espouses values and principles that I cannot support. So within our “English” culture (now there’s a concept freighted with conflict) there are beliefs I certainly don’t share and people whose behaviour I don’t support because they conflict with my ethical and moral system. In the same way there are values and beliefs in other cultures that I cannot support (where women are systematically oppressed, for example or where homosexuality is punished by death). I cannot ignore or defend the idea of so-called ‘honour killing’. An example of how this plays out in practice is shown in recent paper on female genital mutilation in the Journal of Medical Ethics (see here for the full version)

…we highlight a troubling double standard that legitimises comparable genital surgeries in Western contexts while condemning similar procedures in others…

There can be little doubt that we are all struggling with how to manage our personal and cultural backgrounds in a humane and honest way. As psychologists we should, more than most, be aware of these and have the tools to deal with them. But is this self-awareness and self-knowledge enough? In my own case I am more than conscious of the privilege that my sex, ethnicity, education and class give me as I tick all the wrong boxes when it comes to diversity. I cannot change these things nor can atone for them – they are an integral part of me. I can, however, try to apply this self-awareness to ensure that I do not abuse those characteristics to take unfair advantage of anyone. But in our post-modern Zeitgeist that is not enough it seems. We have been told that we need gatekeepers, monitors of language, taste and public presentation, people to guide our thoughts, feelings and behaviours. This is well articulated by Rosanne McLaughlin when discussing how critics and curators are reframing great artists to fit with modern ethical narratives in the visual arts.

Now I am not going all Andrew Tate or Jordan Peterson here. I am well aware that people like me are disproportionately represented in most organisations and professions (although, it should be noted not in clinical psychology in which 80% of the workforce is female – see here). I am also aware that we wield a disproportionate amount of power and influence and that, both historically and currently, people have suffered at the hands of those who abuse their power and position.

So what can I do? If I were in practice and wanted to submit paper to CPF how will they assess (and, just as importantly, how do I assess) whether I have been culturally mindful or not? And this is what is wrong with the editors’ injunction. Unless these statements are operationalised and clarified in behavioural terms they are little other than vacuous feel-good phrases. They are no more than a pious posturing in order to placate our own feelings. It is also dangerous. Such superficial poses feed the reactionary forces that wish to pursue a frankly racist agenda. And this is what really, really gets me angry. That there are serious failings in both society at large and psychology, both historic and current, which need addressing when it comes to matters of equality, fairness and justice is beyond dispute. It is right that we should know about and reflect on the lengths to which our predecessors went (and the depths to which they sank) to exploit people and cultures to feed their (and now, our) appetites and desires (see, for example, the history of nutmeg (Ghosh, 2021)). It is also right that we are aware of the exploitation that goes on to this very day, although rare earths for our electronics have replaced aromatic spices (see, for example, Sebastião Salgado’s photographs and Niarchos (2025)). We need to take a critical stance when we assess past psychological research and ensure that we are not over-interpreting data from limited samples (such as US psychology undergraduates earning course credits for participating). We need to remind ourselves that the world within both our and our clients’ heads is not just a function of internal psychic forces but is influenced by the outside world of society and culture (perhaps all psychology degrees should have mandatory sociology and anthropology modules).

Knowing this stuff is uncomfortable – as it should be. Feeling upset and some sort of empathy for those who have suffered is an understandable humanitarian response to exploitation, pain and distress. We have to be grown-up enough to live with and deal with that discomfort. A mere recitation of fashionable diversity mantras changes nothing. We cannot alter what has happened. Our timeframe in the now and the future. Let us learn from the past and do our level best to ensure that our actions and behaviours do not repeat the exploitative oppression of our forebears.

References

Ahmadu, F.S.N., Bader, D., Boddy, J., et al (2025).Harms of the current global anti-FGM campaign. Journal of Medical Ethics . Published Online First: 14 September 2025. doi: 10.1136/jme-2025-110961

British Psychological Society. (2021). BPS Code of Human Research Ethics. British Psychological Society.

Eagleton, T. (2003). After Theory. Allen Lane.

Ghosh, A. (2021). The Nutmeg’s Curse; Parables for a Planet in Crisis. University of Chicago Press.

Niarchos, N. (2026). The Elements of Power. William Collins.

Salgado, S. (2024). Workers. An Archaeology of the Industrial Age. Taschen.

Salgado, S. (2026). Gold. Taschen.

You can’t make it up! Did he get a fiver for every time he mentioned the word “diversity”.

I’m still looking for my eyebrows!

The comment far less erudite than some of the previous contributions.

LikeLike